Perdido/Achado, an expression through photography workshop with the inmates of Boane Penitentiary Institution.

Perdido/achado is the name that was given (retrospectively) to an expression through photography workshop developed together with twelve inmates of the Boane Juvenile Detention Centre, in early 2022.

I had become familiar with the Mozambican correctional system through some documentation and news reports published in 2020 on Covid-19 prevention methods in three different prisons in the city of Maputo. One of these initiatives involved bringing the prison tailoring workshops up to full capacity so that inmates could produce cloth masks to respond self-sufficiently to the measures imposed by the pandemic. In termes of image-production this approach was part of a dynamic: emergency-documentation-representation.

Both myself and Reformar, research for Mozambique, an organisation that carries out researches on criminal justice in Mozambique, were struck by the same idea: what if the vital space that the tailoring workshops were carving out within the institution could be later occupied also by a photography workshop? It would have been possible to create a space where the roles of those who usually stand in front of and behind the camera could be renegotiated and fluidified. Perhaps we could have initiated a small linguistic operation aimed at sharing a tool that is too often used without questioning the power relations that gravitate around it. We chose to work with the interiors of the Boane Juvenile Detention Centre.

The way in which a camera steps into a penitentiary institution is always a challenge, especially when the “iconifying” power of photography is placed on the side of the inmate, supporting their transformative process and expression, unleashing the wonder of “seeing oneself” again, especially within an institution that tends to contain individual differences and denies people the opportunity to see themselves on mobile phones or other devices. Furthermore, how can we ensure that this space for expression blends in with the rest of the institution without disrupting its vertical and controlled nature?

PERCEPTION

Perhaps before anything else, before the cameras come in, it would be appropriate for the images to enter, printed or “seen” with that pure wonder reserved to reality when we exercise the action of “looking”. Perhaps a photography workshop could be the nucleus of a broader discourse on perception, where the gesture of photographing is conceived as a continuation of pure visual perception, of the simple act of looking. It was necessary to give life to an open, slow process, far from the clamour and acceleration that the “outside” world likes, not specifically based on the codes of a discipline, but rather open to the necessary deviations inspired from time to time by content, signs, and above all words (or pairs of words) emerged along the way.

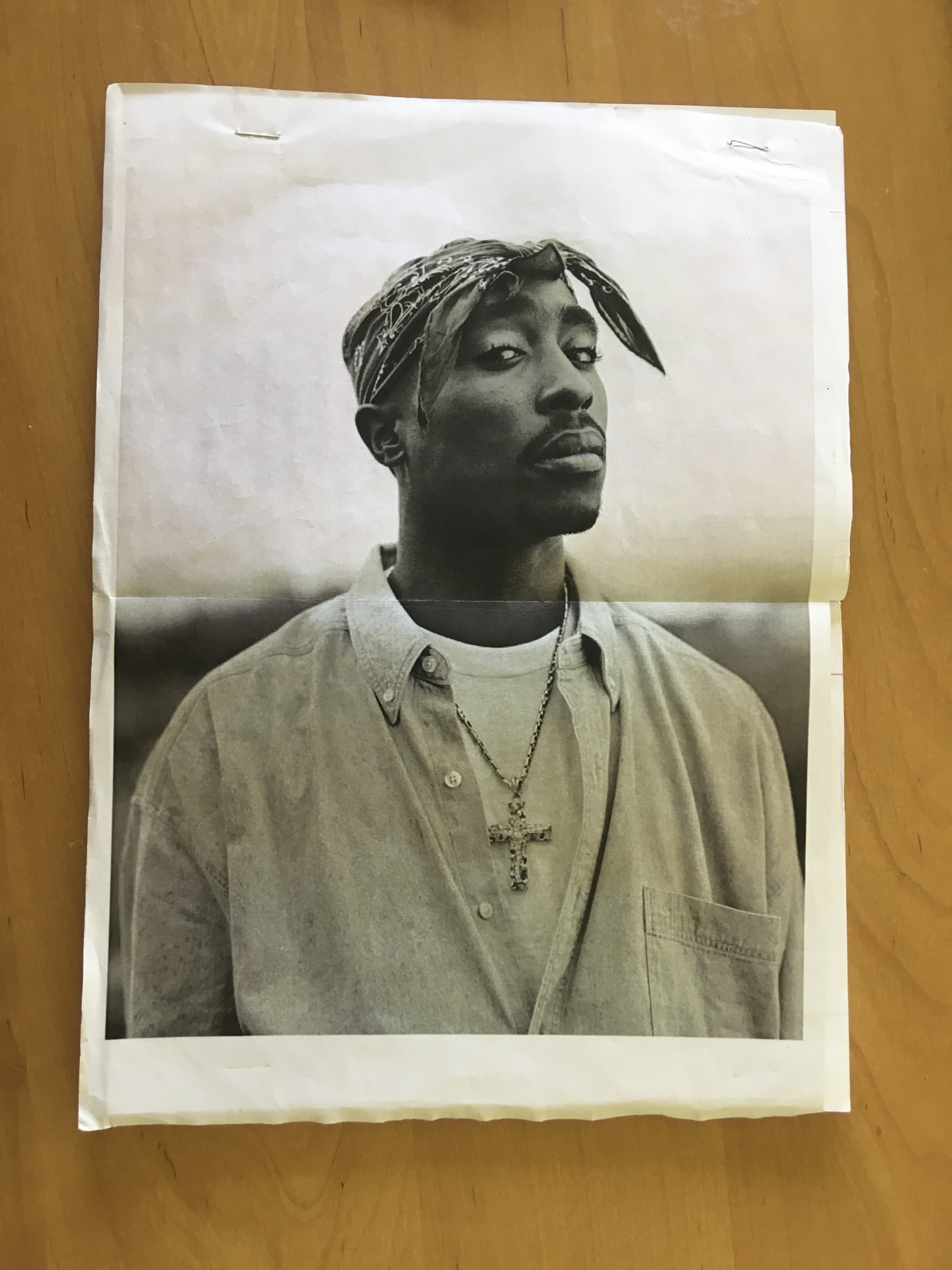

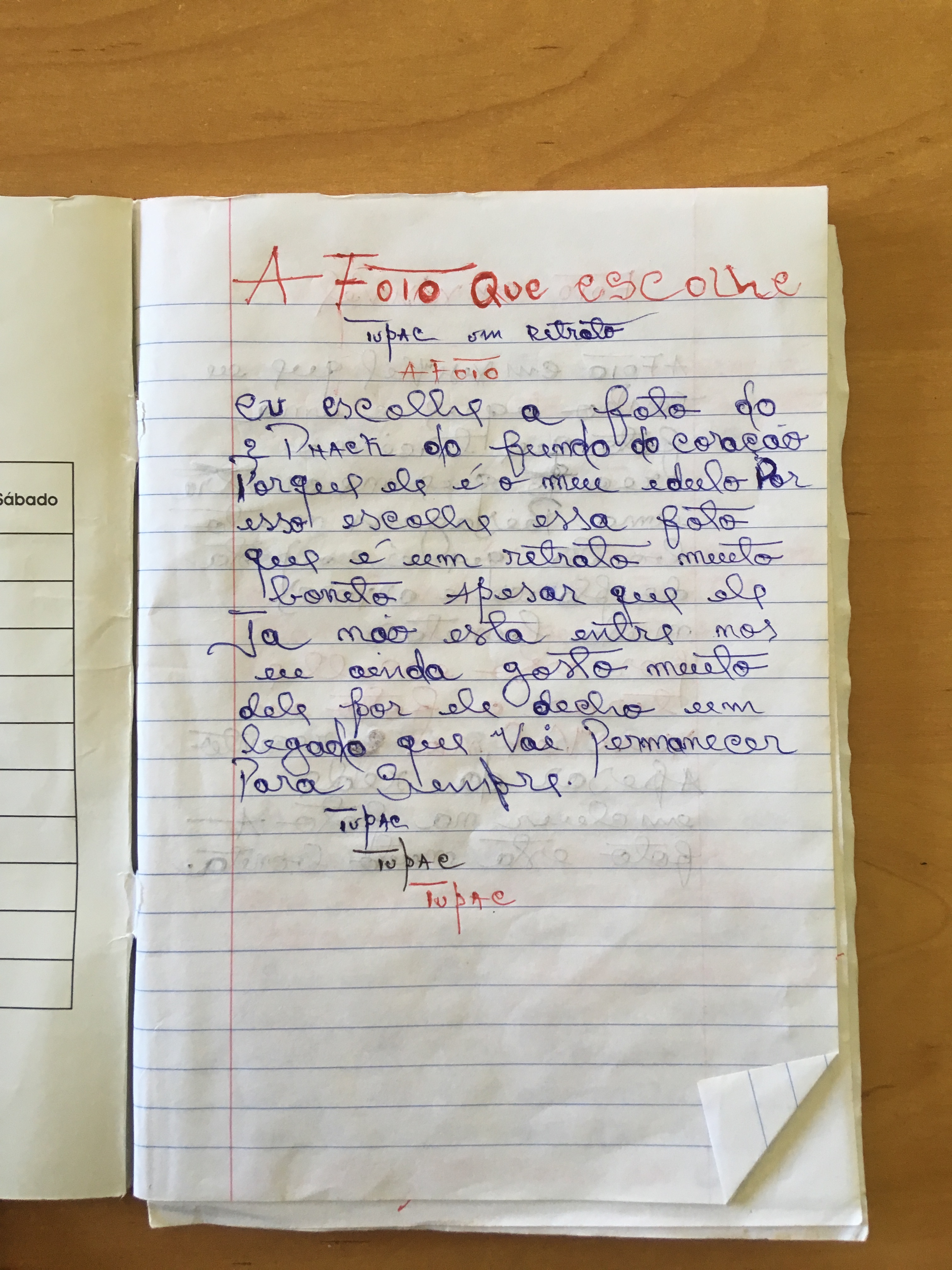

Perdido/achado (Lost/Found), the name subsequently given to the exhibition and the entire project, was inspired by the first exercise in the workshop, which saw images entering the prison. These were nothing more than photocopies of several photographs by renowned artists (Malik Sibidé, Martin Parr, Ricardo Rangel, Dana Lixemberg, Lauren Greenfield) that function as a normal projective exercise used in art therapy, in which the images are placed on the floor and each participant chooses one, talking about the emotions that the photo conveys to them. Here, photography manifests itself in one of its most characteristic tensions, that between lost and found. The first pairs of opposites emerge: lost/found and inside/outside. Everything speaks of an interruption, of a before and after, brought back to light by the power of images. In the “invisible photo” exercise, where we take photos with our eyes (or with a black card) but not yet with a camera, the gaze intercepts spatial thresholds, where portions of space fall “inside” and others “outside”, tracing a connection with the inner discourses that inhabit the minds and hearts of the participants. Far from overstimulating these discourses, we are content for them to emerge as fragments, in written form in their photo-diaries, in the form of a mosaic of written fragments and meaningful images over the passage of time.

Before the camera appears, it may be necessary to explore a practice, revealing a greater human truth that underlies the act of photographing. Isn't photography a way of performing a threshold between oneself and someone else? The connection between photography and performance art is something that drives my research as a visual artist. In this case, I decided to work on this link through the perception exercises of Augusto Boal, founder of the theatre of the oppressed, which he studied and developed in Brazilian prisons. According to Boal, all arts descend from theatre, as it was humanity's first attempt to “observe itself”. Photography is a further attempt, and also carries within it the concept of the spect-actor so dear to Boal. The photographer looks, but the moment he takes the picture, he interacts, performs, changes the environment around him.

Perception exercises transfer sociality to an interactive level, shaking it off the syncretic level on which relationships within the institution are often placed, finally leading to the amazement of the first portrait sessions that take place among the participants, where seeing finally becomes “seeing oneself”, entrusted to the bond between two people.

FROM FIGURATION TO NARRATION.

This article does not aim to reconstruct the entire process that took place within the workshop, especially given that each workshop is unique, nor do we aim to reveal its entire development, and if we do so, it is mainly through the words of its participants. However, we can describe the trajectory of this experience as a transition from figuration to narration, through figures that are also metaphors... as in the still files dedicated to celebrating the day of the “mulher moçambicana” (Mozambican woman).

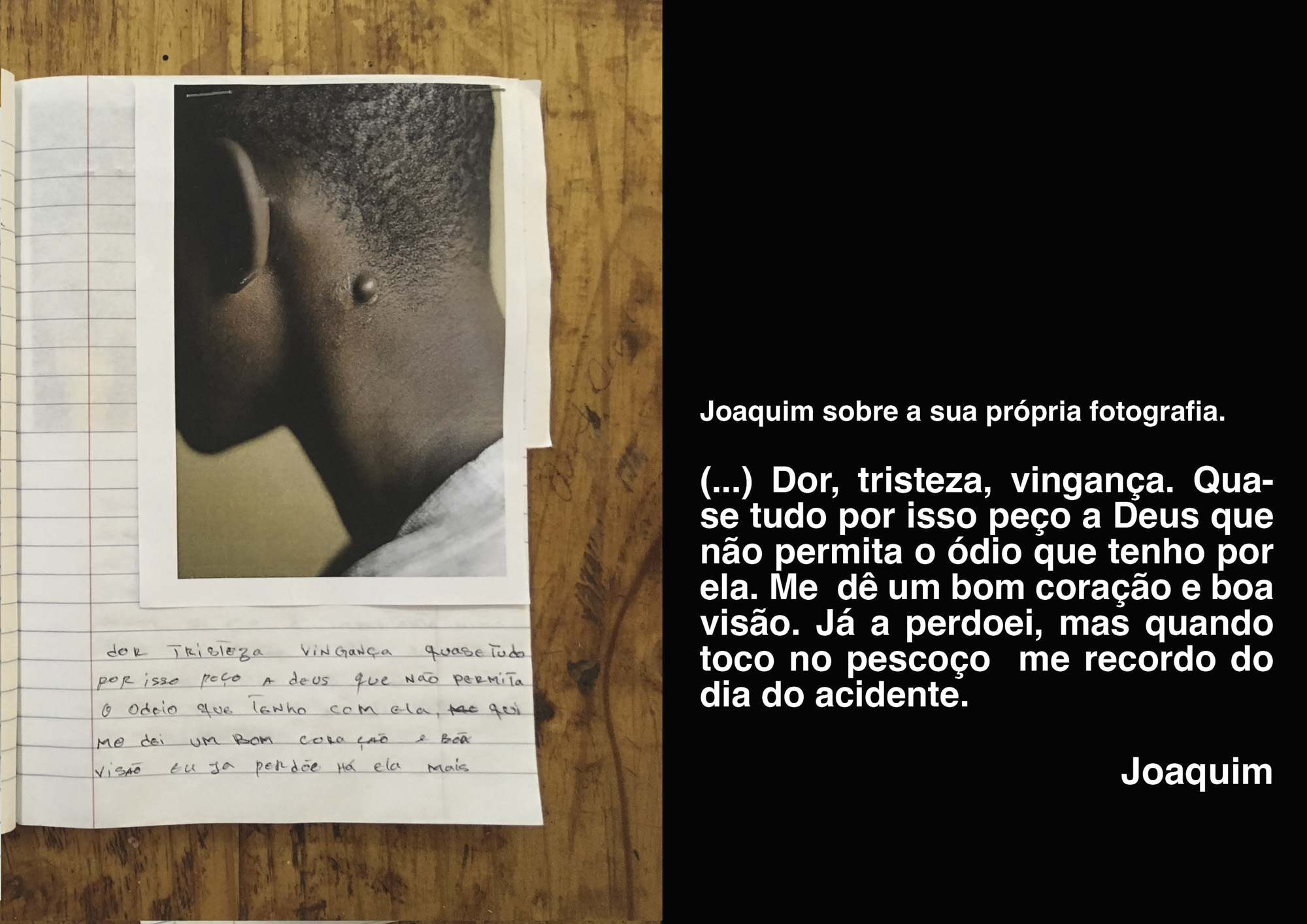

After regaining their perception, participants are ready to use the emotion evoked by the photographs to tell stories, including their own, through “the part for the whole” that inspired the work “scars”. Can a detail, a sign, trigger a small story, release something we carry inside us, even if only in the form of a small poetic fragment?

THE SKY

In general, the space of a prison can be full of limitations: repetitive and minimal architecture, metaphysical corners devoid of surprises. But we know that limitations can also become a resource. Can an environment that offers such basic, minimal spatial concepts lead us more easily to the primary elements of visual perception? Can these elementary concepts become tools for reconstructing or reimagining what is before our eyes? This is how we arrived at the sky. If everything is figure and background, all you need to do is point your camera in the right direction to see only yourself and the sky.

CONCLUSIONS.

The way in which an expression workshop carves out its space within an institution, especially a penitentiary, is always a delicate matter. Institutions and organisations are always repositories of a syncretic sociality (Bleger 1970). This is a silent, unmanifest sociality, established on a layer of the personality not yet identified, different from that which arises through interaction. Syncretic sociality is by its nature undifferentiated, conservative and resistant to change. It aims at repetition, protection and bureaucracy. If social interactions stand out as figures, the syncretic part of sociality constitutes their background. In this case, the figure-background relationships are characterised by a certain fixity and aimed at maintaining the pre-established order, sometimes at the cost of a certain depersonalisation of prisoners and prison officers. The expression workshop therefore introduces the aesthetic experience into a type of environment that could be deliberately defined as anti-aesthetic, for reasons related to its survival. A new dynamic emerges within the institution: some individuals, within the symbolic possibilities offered by the photographic medium, reawaken their perception and begin an activity of figuration. They begin to make contact with themselves in a different way from that usually offered by the institution. They begin to “figure” themselves. Can this rediscovery of the narrative self be put at the service of the institution and its growth? Can this dynamic also have an emancipatory function for the institution as a whole? How can we incorporate the collective dimension into this path of personal growth? The hope is to start a new narrative of the institution created by the inmates themselves, documenting the activities in which they participate and their system of relationships. Obviously, in order to maintain a tendency towards conservation driven by syncretic sociality, it would be more convenient to continue to be told about it from the outside; however, if some positive changes are made following the introduction of an expression workshop, they cannot concern only a small group of people. In a field where every behaviour is the result of the action of a system of forces, the liberating experience of a group of individuals could cause anxiety and closure in other members of the institution. It is precisely in an attempt to rebalance this process that the ultimate goal of putting the expressive abilities rediscovered by the subjects back at the service of the community arises. Specifically, this would be achieved by creating a collective, superordinate figure: an institution that determines its own narrative, documenting its activities and efforts through the eyes of the inmates, who become narrators, journalists and chroniclers of their own rehabilitation. This is not merely a matter of optimising resources, but of reversing a well-established cultural perspective regarding who narrates what/who narrates whom. It is about constructing a real counter-narrative of the penitentiary institution carried out by the institution itself, an operation which, if well coordinated across several institutions, could generate a first large archive of images and stories by inmates transformed into spect-actors.